EMERGING DYNAMICS

INTERNATIONAL: MORE CONTESTED, UNCERTAIN, AND CONFLICT PRONE

Key Takeaways

- During the next two decades, power in the international system will evolve to include a broader set of sources and features with expanding technological, network, and information power complementing more traditional military, economic, and cultural soft power. No single state is likely to be positioned to dominate across all regions or domains, opening the door for a broader range of actors to advance their interests.

- The United States and China will have the greatest influence on global dynamics, supporting competing visions of the international system and governance that reflect their core interests and ideologies. This rivalry will affect most domains, straining and in some cases reshaping existing alliances, international organizations, and the norms and rules that have underpinned the international order.

- In this more competitive global environment, the risk of interstate conflict is likely to rise because of advances in technology and an expanding range of targets, new frontiers for conflict and a greater variety of actors, more difficult deterrence, and a weakening or a lack of treaties and norms on acceptable use.

(INTERNATIONAL DYNAMICS - Click image to enlarge)

These power dynamics are likely to produce a more volatile and confrontational geopolitical environment, reshape multilateralism, and widen the gap between transnational challenges and cooperative arrangements to address them.

During the next two decades, the intensity of competition for global influence is likely to reach its highest level since the Cold War. No single state is likely to be positioned to dominate across all regions or domains, and a broader range of actors will compete to advance their ideologies, goals, and interests. Expanding technological, network, and information power will complement more traditional military, economic, and soft power aspects in the international system. These power elements, which will be more accessible to a broader range of actors, are likely to be concentrated among leaders that develop these technologies.

These power dynamics are likely to produce a more volatile and confrontational geopolitical environment, reshape multilateralism, and widen the gap between transnational challenges and cooperative arrangements to address them. Rival powers will jockey to shape global norms, rules, and institutions. The United States, along with its longstanding allies, and China will have the greatest influence on global dynamics, supporting competing visions of the international system and governance that reflect their core interests and ideologies. Their rivalry will affect most domains, straining and in some cases reshaping existing alliances and international organizations that have underpinned the international order for decades.

Accelerating power shifts—as well as hardening ideological differences and divisions over governance models—are likely to further ratchet up competition. The rivalry is unlikely to resemble the US-Soviet rivalry of the Cold War, however, because of the greater variety of actors in the international system that can shape outcomes, interdependence in various domains, and fewer exclusive ideological dividing lines. The lack of a preponderant power or global consensus on some key areas will offer opportunities for other actors to lead or pursue their own interests, especially within their regions. The European Union (EU), India, Japan, Russia, and the United Kingdom most likely will also be consequential in shaping geopolitical and economic outcomes.

This more competitive environment with rapidly emerging technologies is likely to be more volatile with a heightened risk of conflict, at least until states establish new rules, norms, and boundaries for the more disruptive areas of competition. States will face a combination of highly destructive and precise conventional and strategic weapons, cyber activity targeting civilian and military infrastructure, and a confusing disinformation environment. Regional actors, including spoilers such as Iran and North Korea, will jockey to advance their goals and interests, bringing more volatility and uncertainty to the system. At the same time, states may struggle to establish stable deterrence with these new systems, particularly if the rules and treaties governing them continue to erode or lag.

CHANGING SOURCES AND COMPOSITION OF POWER

During the next 20 years, sources of power in the international system are likely to expand and redistribute. Material power, measured by the size of a nation’s economy, military, and population, and its technological development level, will provide the necessary foundation for exercising power, but will be insufficient for securing and maintaining favorable outcomes. In an even more hyperconnected world, power will include applying technology, human capital, information, and network position to modify and shape the behavior of other actors, including states, corporations, and populations. The attractiveness of a country’s entertainment, sports, tourism, and educational institutions will also remain important drivers of its influence. As global challenges such as extreme weather events and humanitarian crises intensify, building domestic resiliency to shocks and systemic changes will become a more important element of national power, as will a state’s ability and willingness to help other countries. In coming years, the countries and nonstate actors that are best able to harness and integrate material capabilities with relationships, network centrality, and resiliency will have the most meaningful and sustainable influence globally.

Material Power. Military capabilities and economic size will remain the foundation of state capacity and power projection, compelling other countries to take a state’s interests and policies into account. These two areas of power allow states to maintain their security and to amass resources that enable other elements of power.

Technology Power. Technology, particularly military technologies, will continue to be central to a country’s security and global influence, but going forward, cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology, and data-driven decisionmaking will provide states with a range of advantages for economic growth, manufacturing, healthcare, and societal resiliency. With these technologies, there will be a first mover advantage, enabling states and nonstate actors to shape the views and decisionmaking of populations, to gain information advantages over competitors, and to better prepare for future shocks.

Human Capital. Favorable demographics, including a strong working-age population, universal basic education, and a concentration of science, engineering, math, and critical thinking skills, will provide large advantages for innovation, technological advancement, economic growth, and resiliency. Regions with large working-age populations, including in Latin America and South Asia, will have new sources of potential economic strength if they can improve education, skillsets, and infrastructure; aging and contracting societies in Europe and Asia will need to find ways to augment their workforce to avoid seeing this element of power weakened.

Networks and Nodes. Control of key sites of exchange, including telecommunications, finance, data flows, and manufacturing supply chains, will give countries and corporations the ability to gain valuable information, deny access to rivals, and even coerce behavior. Many of these networks, which are disproportionately concentrated in the United States, Europe, and China, have become entrenched over decades and probably will be difficult to reconfigure. If China’s technology companies become co-dominant with US or European counterparts in some regions or dominate global 5G telecommunications networks, for example, Beijing could exploit its privileged position to access communications or control data flows. Exercising this form of power coercively, however, risks triggering a backlash from other countries and could diminish the effectiveness over time.

Information and Influence. Compelling ideas and narratives can shape the attitudes and priorities of other actors in the international system, and they can legitimize the exercise of other types of power. The soft power attractiveness of a society, including its culture, entertainment exports, sports, lifestyles, and technology innovations, can also capture the imagination of other populations. Tourism and education abroad—particularly higher education—can increase the attractiveness. From public diplomacy and media to more covert influence operations, information technologies will give governments and other actors unprecedented abilities to reach directly to foreign publics and elites to influence opinions and policies. China and Russia probably will try to continue targeting domestic audiences in the United States and Europe, promoting narratives about Western decline and overreach. They also are likely to expand in other regions, for example Africa, where both have already been active.

Resiliency. As the world has become more deeply interconnected, systemic shocks are becoming more common and more intense, spawning many second-order effects. Governments that are able to withstand, manage, and recover from shocks and that have domestic legitimacy will have better capacity to project power and influence abroad. Building resiliency, however, depends on a reservoir of trust within societies and between populations and leaders, and is likely to be more difficult to muster as societies become more fractured.

MORE ACTORS ASSERTING AGENCY

As sources of power expand and shift globally, the actors and the roles they play in shaping global dynamics will also change. No single actor will be positioned to dominate across all regions and in all domains, offering opportunities for a broader array of actors and increasing competition across all issues. The growing contest between China and the United States and its close allies is likely to have the broadest and deepest impact on global dynamics, including global trade and information flows, the pace and direction of technological change, the likelihood and outcome of interstate conflicts, and environmental sustainability. Even under the most modest estimates, Beijing is poised to continue to make military, economic, and technological advancements that shift the geopolitical balance, particularly in Asia.

China Reclaiming Global Power Role

In the next two decades, China almost certainly will look to assert dominance in Asia and greater influence globally, while trying to avoid what it views as excessive liabilities in strategically marginal regions. In Asia, China expects deference from neighbors on trade, resource exploitation, and territorial disputes. China is likely to field military capabilities that put US and allied forces in the region at heightened risk and to press US allies and partners to restrict US basing access. Beijing probably will tout the benefits of engagement while warning of severe consequences of defiance. China’s leaders almost certainly expect Taiwan to move closer to reunification by 2040, possibly through sustained and intensive coercion.

China will work to solidify its own physical infrastructure networks, software platforms, and trade rules, sharpening the global lines of techno-economic competition and potentially creating more balkanized systems in some regions. China is likely to use its infrastructure and technology-led development programs to tie countries closer and ensure elites align with its interests. China probably will continue to seek to strengthen economic integration with partners in the Middle East and Indian Ocean region, expand its economic penetration in Central Asia and the Arctic, and work to prevent countervailing coalitions from emerging. China is looking to expand exports of sophisticated domestic surveillance technologies to shore up friendly governments and create commercial and data-generating opportunities as well as leverage with client regimes. China is likely to use its technological advancements to field a formidable military in East Asia and other regions but prefers tailored deployments—mostly in the form of naval bases—rather than large troop deployments. At the same time, Beijing probably will seek to retain some important linkages to US and Western-led networks, especially in areas of greater interdependence such as finance and manufacturing.

China is likely to play a greater role in leading responses to confronting global challenges commensurate with its increasing power and influence, but Beijing will also expect to have a greater say in prioritizing and shaping those responses in line with its interests. China probably will look to other countries to offset the costs of tackling transnational challenges in part because Beijing faces growing domestic problems that will compete for attention and resources. Potential financial crises, a rapidly aging workforce, slowing productivity growth, environmental pressures, and rising labor costs could challenge the Chinese Communist Party and undercut its ability to achieve its goals. China’s aggressive diplomacy and human rights violations, including suppression of Muslim and Christian communities, could limit its influence, particularly its soft power.

Other Major Powers

Other major powers, including Russia, the EU, Japan, the United Kingdom, and potentially India, could have more maneuvering room to exercise influence during the next two decades, and they are likely to be consequential in shaping geopolitical and economic outcomes as well as evolving norms and rules.

Russia is likely to remain a disruptive power for much or all of the next two decades even as its material capabilities decline relative to other major players. Russia’s advantages, including a sizeable conventional military, weapons of mass destruction, energy and mineral resources, an expansive geography, and a willingness to use force overseas, will enable it to continue playing the role of spoiler and power broker in the post-Soviet space, and at times farther afield. Moscow most likely will continue trying to amplify divisions in the West and to build relationships in Africa, across the Middle East, and elsewhere. Russia probably will look for economic opportunity and to establish a dominant military position in the Arctic as more countries step up their presence in the region. However, with a poor investment climate, high reliance on commodities with potentially volatile prices, and a small economy—projected to be approximately 2 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) for the next two decades—Russia may struggle to project and maintain influence globally. President Vladimir Putin’s departure from power, either at the end of his current term in 2024 or later, could more quickly erode Russia’s geopolitical position, especially if internal instability ensues. Similarly, a decrease in Europe’s energy dependence on Russia, either through renewables or diversifying to other gas suppliers, would undercut the Kremlin’s revenue generation and overall capacity, especially if those decreases could not be offset with exports to customers in Asia.

The EU’s large market and longstanding leadership on international norms will enable it to retain significant influence in coming decades, especially if it can prevent additional members from departing and can reach consensus on a common strategy for navigating global competition and transnational challenges. The economic weight of the EU’s single market almost certainly will continue to give it global geopolitical clout on trade, sanctions, technology regulations, and environmental and investment policies. Countries outside the EU often model their standards and regulations on EU policies. European military strength is likely to fall short of some members’ ambitions because of competing priorities and long-term underinvestment in key capabilities. European defense expenditures will compete with other post–COVID-19 fiscal priorities, and its security initiatives are unlikely to produce a military capability separate from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization that can defend against Russia.

The United Kingdom is likely to continue to punch above its weight internationally given its strong military and financial sector and its global focus. The United Kingdom’s nuclear capabilities and permanent UN Security Council membership add to its global influence. Managing the economic and political challenges posed by its departure from the EU will be the country’s key challenge; failure could lead to a splintering of the United Kingdom and leave it struggling to maintain its global power.

Japan’s highly educated population, technologically innovative economy, and integral position in trade and supply chain networks position it to remain a strong power in Asia and beyond. Japan is likely to remain highly economically dependent on its largest trading partner and main regional rival China and a close ally of the United States while working to further diversify security and economic relationships, particularly with Australia, India, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Japan will also face mounting demographic and macroeconomic challenges, including a shrinking labor force—the oldest of any developed country—with inflexible immigration policies, low demand and economic growth, deflation, declining savings rates, and increased government debt.

India’s population size—projected to become the largest in the world by 2027—geography, strategic arsenal, and economic and technological potential position it as a potential global power, but it remains to be seen whether New Delhi will achieve domestic development goals to allow it to project influence beyond South Asia. As China and the United States compete, India is likely to try to carve out a more independent role. However, India may struggle to balance its long-term commitment to strategic autonomy from Western powers with the need to embed itself more deeply into multilateral security architectures to counter a rising China. India faces serious governance, societal, environmental, and defense challenges that constrain how much it can invest in the military and diplomatic capabilities needed for a more assertive global foreign policy.

Regional Powers Seeking Greater Influence

In this competitive environment, regional powers, such as Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, Iran, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), probably will seek to take advantage of new opportunities and to take on roles previously filled by a major power to shore up regional stability or gain influence. This mix of regional powers seeking greater roles and influence is likely to change during the next two decades, reflecting opportunities as well as the changing capabilities and leadership goals of various states. Regional powers probably will try to play major powers off each other to maximize rewards while attempting to avoid being drawn into unwanted conflicts. They may seek to build their own coalitions or strengthen regional blocs to project influence and in some cases, collaborate on global challenges, but in other cases they may act more aggressively in conflicts in their region. Overcoming domestic governance challenges, recovering quickly from the COVID-19 pandemic and other shocks, and managing relationships with neighbors will be crucial for converting their key strengths into increased influence. Some probably will play crucial roles in tackling challenges at the regional level including nonstate actor security threats, terrorism, mass migration, and digital privacy.

Nonstate Actors Powerful, Influential

Nonstate actors, such as NGOs, religious groups, and technology superstar firms, will have the resources and global reach to build and promote alternative networks that complement, compete with, or possibly bypass states. In the past several decades, nonstate actors and transnational movements have used growing international connections for collective action or to influence populations around the world. In some cases, these actors can shape or constrain state actions through lobbying leaders and mobilizing citizens. The influence of nonstate actors will vary and be subject to government intervention. China, the EU, and others are already moving to regulate or break up superstar firms, while Beijing is trying to control or suppress NGOs and religious organizations. Many nonstate actors are likely to try to push back on state efforts to consolidate sovereignty in newer frontiers, including cyberspace and space.

GEOPOLITICAL COMPETITION INTENSIFYING AI-POWERED PROPAGANDA

The growth in global digital connectivity, immersive information technology, and widely accessible digital marketing techniques opens the potential for greater information influence activities against almost all societies.

Both states and nonstate actors almost certainly will be able to use these tools to influence populations, including by ratcheting up cognitive manipulation and societal polarization to shape how people receive, interpret, and act on information. Countries, including China and Russia, are likely to apply technological innovations to make their information campaigns more agile, difficult to detect, and harder to combat, as they work to gain greater control over media content and means of dissemination.

Governments and nonstate actors are increasingly able to exploit consumer behavior data and marketing techniques to microtarget messages to small audience segments. Propagandists could leverage AI, the Internet of Things, and other tools to tailor communications to large audiences, anticipate their reactions, and adapt messaging in near real time.

Behavioral big data, which captures statistical patterns in human psychology and action, may also enable significant predictive power and capacity for personalized influence. If meaningful regulation does not exist, public relations firms and political consultants can offer disinformation as a regular service, increasing public distrust in political institutions.

CONTESTED AND TRANSFORMING INTERNATIONAL ORDER

As global power continues to shift, many of the relationships, institutions, and norms that have largely governed and guided behavior across issues since the end of the Cold War are likely to face increasing challenges. Competition in these areas has been on the rise for years with China, Russia, and other countries demanding a greater say. Disagreements are likely to intensify over the mission and conduct of these institutions and alliances, raising uncertainty about how well equipped they will be to respond to traditional and emerging issues. Over time, states may even abandon some aspects of this international order.

Rising and revisionist powers, led by China and Russia, are seeking to reshape the international order to be more reflective of their interests and tolerant of their governing systems. China and Russia continue to advocate for an order devoid of Western-origin norms that allows them to act with impunity at home and in their perceived spheres of influence. They are advocating for alternative visions of the role of the state and human rights and are seeking to roll back Western influence, but their alternative models differ significantly from each other. Russia is promoting traditional values and desires a Russian-dominated protectorate covering much of Eurasia. China seeks growing global acceptance of its current social system—namely the Chinese Communist Party’s monopoly on power and control over society—socialist market economy, and preferential trading system.

Increasing Ideological Competition

The multidimensional rivalry with its contrasting governing systems has the potential to add ideological dimensions to the power struggle. Although the evolving geopolitical competition is unlikely to exhibit the same ideological intensity as the Cold War, China’s leadership already perceives it is engaged in a long-term ideological struggle with the United States. Ideological contests most often play out in international organizations, standard-setting forums, regional development initiatives, and public diplomacy narratives.

Western democratic governments probably will contend with more assertive challenges to the Western-led political order from China and Russia. Neither has felt secure in an international order designed for and dominated by democratic powers, and they have promoted a sovereignty-based international order that protects their absolute authority within their borders and geographic areas of influence. China and Russia view the ideas and ideology space as opportunities to shape the competition without the need to use military force. Russia aims to engender cynicism among foreign audiences, diminish trust in institutions, promote conspiracy theories, and drive wedges in societies. As countries and nonstate actors jockey for ideological and narrative supremacy, control over digital communications platforms and other vehicles for dissemination of information will become more critical.

Relationships Facing More Tradeoffs

In this more competitive geopolitical environment, many countries would prefer to maintain diverse relationships, particularly economic ties, but over time, actions by China, Russia, and others may present starker choices over political, economic, and security priorities and relationships. Some countries may gravitate toward looser, more ad hoc arrangements and partnerships that provide greater flexibility to balance security concerns with trade and economic interests. Longstanding security alliances in Europe and Asia are facing growing strains from a confluence of domestic perceptions of security threats, concerns about partner reliability, and economic coercion. That said, if China and Russia continue to ratchet up pressure, their actions may resolidify or spawn new security relationships among democratic and like-minded allies, enabling them to put aside differences.

China and Russia probably will continue to shun formal alliances with each other and most other countries in favor of transactional relationships that allow them to exert influence and selectively employ economic and military coercion while avoiding mutual security entanglements. China and Russia are likely to remain strongly aligned as long as Xi and Putin remain in power, but disagreements over the Arctic and parts of Central Asia may increase friction as power disparities widen in coming years.

Contestation Weakening Institutions

Many of the global intergovernmental organizations that have underpinned the Western-led international order for decades, including the UN, World Bank, and World Trade Organization (WTO), are bogged down by political deadlock, decreasing capacity relative to worsening transnational challenges and increasing country preferences for ad hoc coalitions and regional organizations. Most of these organizations are likely to remain diplomatic battlegrounds and to become hollowed out or sidelined by rival powers.

Looking forward, these global institutions are likely to continue to lack the capacity, member buy-in, and resources to help effectively manage transnational challenges, including climate change, migration, and economic crises. In many cases, these challenges exceed the institutions’ original mandates. Members’ rising fiscal challenges could translate into diminished contributions, and sclerotic decisionmaking structures and entrenched interests will limit the ability to reform and adapt institutions. These institutions probably will work with and in some cases in parallel with regional initiatives and other governance arrangements, such as the epidemic response in Sub-Saharan Africa, infrastructure financing in Asia, and artificial intelligence (AI) and biotechnology governance. The future focus and effectiveness of established international organizations depend on the political will of members to reform and resource the institutions and on the extent to which established powers accommodate rising powers, particularly China and India. The WTO probably will face considerable uncertainty about its future role and capacity to foster greater cooperation and open trade as states become more protectionist and rival blocs square off against each other. In contrast, the unique role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and high demand for IMF conditionality and assistance in debt restructuring most likely will make it central to the international system, although the growth of sovereign debt outside IMF purview will be a challenge. Similarly, multistakeholder agreements and organizations that regulate the global financial, insurance, or technical systems such as the Basel Accords and Internet Engineering Task Force are likely to remain in high demand.

Western leadership of the intergovernmental organizations may further decline as China and Russia obstruct Western-led initiatives and press their own goals. China is working to re-mold existing international institutions to reflect its development and digital governance goals and mitigate criticism on human rights and infrastructure lending while simultaneously building its own alternative arrangements to push development, infrastructure finance, and regional integration, including the Belt and Road Initiative, New Development Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. In the past five years, Moscow has tried to undermine international efforts to strengthen safeguards and monitor for chemical weapons and has used the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) to pursue opponents.

Continued underperformance of many of the global multilateral institutions is likely to shift some focus to alternative informal, multi-actor arrangements, such as the G5 Sahel Joint Force to counter extremists in the Sahel, the global vaccine alliance, and the global initiative to bring greater transparency to extractive industries. Some of these show promise in filling crucial capacity gaps, but their long-term impact will depend on marshalling the resources, political buy-in, and leadership from major and regional powers. Some regions, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and Southeast Asia, are likely to continue moves to strengthen regional organizations and integration, whereas other regions are likely to struggle to cooperate because of lingering inter-state divisions.

Standards as a Battlespace

International standards agreements support the emergence of new technologies by reducing market uncertainty and establishing norms. Membership on standard-setting bodies is increasingly competitive, largely because of the influence these bodies have on how and which technologies enter the market, and thereby, which technology producers gain advantage. Long dominated by the United States and its allies, China is now moving aggressively to play a bigger role in establishing standards on technologies that are likely to define the next decade and beyond. For example, international standard-setting bodies will play critical roles in determining future ethical standards in biotechnology research and applications, the interface standards for global communication, and the standards for intellectual property control.

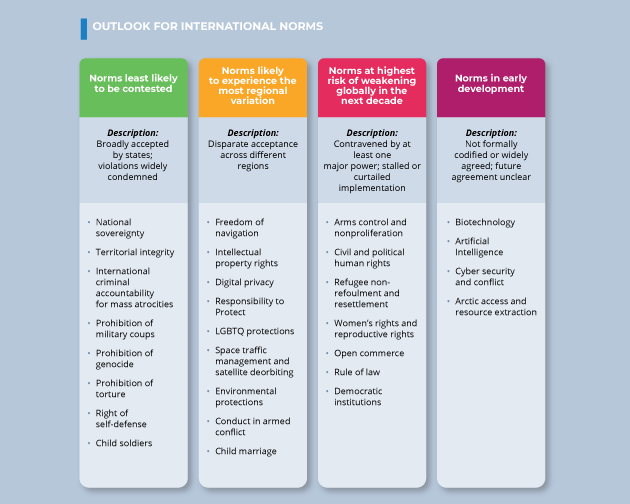

Competition Over Global Norms

A broad set of actors will increasingly compete to promote and shape widely shared global norms ranging from respect for human rights and democratic institutions to conduct in warfare. Some democracies that experienced populist backlashes have backed away from their longstanding roles as champions of norms protecting civil liberties and individual rights. At the same time, authoritarian powers, led by China and Russia, have gained traction as they continue to emphasize their values and push back on norms they view as Western-centric—particularly those that gained currency after the end of the Cold War, such as exceptions that allow for interfering in the internal affairs of member states to defend human rights.

During the next 20 years, this competition probably will make it harder to maintain commitment to many established norms and to develop new ones to govern behavior in new domains, including cyber, space, sea beds, and the Arctic. Existing institutions and norms are not well designed for evolving areas such as biotechnology, cyber, and environmental response and for the growing number of new actors operating in space. Many norm-setting efforts may shift from consensus-based, universal membership institutions to non-global formats, including smaller and regionally-led initiatives. Alternatively, new norms might gain momentum if states collectively perceive growing risks of unilateral action or if increasingly powerful nonstate actors throw their weight behind new guidelines, particularly regarding the use of emerging technologies.

(FUTURE OF INTERNATIONAL NORMS - Click image to enlarge)

INCREASING RISK OF INTERSTATE CONFLICT

In this more competitive global environment, the risk of interstate conflict is likely to rise because of advances in technology and an expanding range of targets, a greater variety of actors, more difficult dynamics of deterrence, and weakening or gaps in treaties and norms on acceptable use. Major power militaries are likely to seek to avoid high-intensity conflict and particularly full-scale war because of the prohibitive cost in resources and lives, but the risk of such conflicts breaking out through miscalculation or unwillingness to compromise on core issues is likely to increase.

(RISK OF MAJOR POWER CONFLICT - Click image to enlarge)

Changing Character of Conflict

Rapidly advancing technologies, including hypersonics and AI, are creating new or enhanced types of weapons systems while offering a wider array of potential targets, across military and civilian capabilities and including domestic infrastructure, financial systems, cyber, and computer networks. These technologies will give states a broader spectrum of coercive tools that fall below the level of kinetic attacks, which many states may be likely to favor as a means of achieving strategic effects while avoiding the political, economic, and human costs of direct violence and declaring hostilities. The result may be further muddied distinctions between sharpened competition and conflict, increasing the motivations for states to establish supremacy at each level of the escalation ladder.

Better sensors, automation, AI, hypersonic capabilities, and other advanced technologies will produce weapons with greater accuracy, speed, range, and destructive power, changing the character of conflict during the next 20 years. Although advanced militaries will have greater access to these advanced capabilities, some weapons are likely to come within reach of smaller states and nonstate actors. The proliferation and diffusion of these systems over time are likely to make more civilian and military systems vulnerable, heighten the risk of escalation, potentially weaken deterrence, and make combat potentially more deadly, although not necessarily more decisive. In a prolonged, large-scale conflict between major powers, some advanced military technologies may begin to have a diminishing impact on the battlefield as expensive and difficult to quickly replace high-end systems are damaged or destroyed or, in the case of munitions, expended in combat. Advanced sensors and weapons will aid in counterinsurgency efforts to identify and target insurgent forces, but these systems may not be sufficient to achieve decisive results given the already asymmetric nature of such conflicts.

(SPECTRUM OF CONFLICT - Click image to enlarge)

Dominance in major power competition and more specifically on the battlefield may increasingly depend on harnessing and protecting information and connecting military forces. Belligerents are increasingly likely to target their adversaries’ computer networks, critical infrastructure, electromagnetic spectrum, financial systems, and assets in space, threatening communications and undermining warning functions. The number and quality of sensors for observation will increase as will the challenges for making sense of and using information. Some governments will be able to manipulate information against their rivals with more precision at scale.

Increasing sensors and connectivity will also make militaries and governments more vulnerable to cyber and electromagnetic attacks. The development of cyber weapons, doctrine, and procedures in conjunction with other weapons is likely to mature significantly during the next 20 years, increasing the consequences of cyber conflict. Countries that can disperse their networks and important warfighting assets, shorten decisionmaking processes, and build in redundancy at every level are likely to be better positioned for future conflicts.

Interstate kinetic conflicts—defined as direct engagement between the military forces of two or more adversaries in which at least one participant suffers substantial casualties or damage—are likely to escalate faster and with less warning than before, compressing response times and increasing pressure to delegate or even automate certain decisionmaking. Inexpensive sensors and data analytics could revolutionize real-time detection and processing by 2040, but many militaries most likely will still struggle to distill meanings and compile options for policymakers without AI and other algorithmic decisionmaking aids. This increased speed is likely to heighten the risk of miscalculation or inadvertent escalation to full-scale war.

(INTRASTATE VERSUS INTERSTATE CONFLICT TRENDS - Click image to enlarge)

Additional Players

Some state-to-state conflicts and international interventions in local conflicts are likely to involve more armed proxies, private military companies, hackers, and terrorist organizations as governments seek to reduce risks and costs for conducting attacks. Proxies and private companies can reduce the cost of training, equipping, and retaining specialized units and provide manpower for countries with declining populations. Some groups can more quickly achieve objectives with smaller footprints and asymmetric techniques. Russia and Turkey have used private and proxy groups in conflicts in Libya and Syria, and private firms have provided a wide range of logistical and other services for coalition forces in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries.

More Difficult Deterrence

The introduction of nonkinetic and nontraditional weapons, new frontiers, and more players is likely to complicate deterrence paradigms and blur escalation redlines. Deterrence strategies rely on the prospect of harm to persuade an opponent to not engage in a specified behavior. These strategies have always been difficult to sustain outside of nuclear warfare, and new forms of attack—cyber and information operations, for example—will add to the challenge. Compounding the challenge, many countries lack clear doctrines for new military capabilities—including conventional, weapons of mass destruction, and asymmetric—to guide their use and develop shared understandings for deterrence. Advancements in conventional and hypersonic weapons; ballistic missile defense; robotics and automated systems; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance networks; and long-range antiship missiles almost certainly will further complicate deterrence calculations and could lead to asymmetric retaliation. Leaders might calculate that they need to strike first in a crisis to avoid losing advanced weapons to a surprise attack.

GROWING CHANCE OF NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION OR EVEN NUCLEAR USE

Nuclear proliferation and potentially nuclear use are more likely in this competitive geopolitical environment. Advances in technology and diversification of delivery systems, arms control uncertainties, and spread of knowledge and skills related to nuclear technology add to the higher risk.

Countries that have declared their nuclear weapons are adding to or upgrading their arsenals; China and Russia are investing in new delivery vehicles including missiles, submarines, bombers, and hypersonic weapons. These states are likely to continue to field increasingly accurate, lower yield nuclear weapons on platforms intended for battlefield use, which could encourage states to consider nuclear use in more instances with doctrines that differentiate between large-scale nuclear exchanges and “limited use” scenarios.

Perceived external security threats are increasing in many regions, particularly the Middle East and Asia, which is a key factor in states’ decision to develop nuclear weapons, according to academic research. Growing questions about security guarantees, extended deterrence, and heightened regional pressures could lead some advanced economies to acquire or build their own programs.

Arms Control and Treaties on the Brink

Existing norms and treaties governing the use of arms and conduct of war are increasingly contested, and new understandings are lagging behind technological innovations. Repeated and unpunished violations of rules and norms on nonviolability of borders, assassination, and use of certain prohibited weapons, like chemical weapons, are shifting actors’ cost-benefit analysis in favor of their use. Renewed competition, accusations of cheating, and the suspension or nonrenewal of several major agreements are likely to weaken strategic arms control structures and undermine nonproliferation.

Reaching agreement on new treaties and norms for certain weapons most likely will be more difficult for these reasons and because of the increasing number of actors possessing these weapons. Weapons considered to have strategic impact probably will no longer be confined to nuclear weapons as conventional weapon capabilities improve and new capabilities, such as long-range precision strike that could put at risk national leadership, offer powerful effects. Countries may struggle to reach agreement on limiting the disruptive or security aspects of AI and other technology because of definitional differences, dual-use commercial applications, and reliance on commercial and often international entities to develop new systems. Incentives for such rules and enforcement mechanisms could emerge over time, especially if crises unfold that showcase the big risks and costs of unrestrained arms development.