EMERGING DYNAMICS

STATE: TENSIONS, TURBULENCE, AND TRANSFORMATION

Key Takeaways

- Governments in all regions will face mounting pressures from economic constraints and a mix of demographic, environmental, and other challenges. Meanwhile, populations will demand more, and they are empowered to push for their conflicting goals and priorities.

- The relationships between societies and their governments are likely to face persistent tensions because of a growing mismatch between what publics expect and what governments deliver. This widening gap portends more political volatility, risks for democracy, and expanding roles for alternative sources of governance.

- Growing public discontent, if accompanied by a catalyzing crisis and inspired leadership, could spur significant shifts or transformations in how people govern.

(STATE DYNAMICS - Click image to enlarge)

While populations are exercising more potent public voices, governments will experience mounting pressure from economic constraints and a mix of demographic, environmental, and other challenges.

GROWING MISMATCH BETWEEN PUBLIC DEMANDS AND GOVERNMENT CAPABILITIES

Over the next two decades, the relationships between states and their societies in every region are likely to face persistent tensions because of a growing mismatch between what publics need or expect and what governments can or are willing to deliver. In many countries, populations with expectations heightened by previous prosperity are likely to face greater strains and disruptions from slowing economic growth, uncertain job opportunities, and changing demographics. These populations also will be better equipped to advocate for their interests after decades of steady improvements in education and access to communication technologies as well as the greater coherence of like-minded groups. Although trust in government institutions is low among the mass public, people are likely to continue to view the state as ultimately responsible for addressing their challenges, and to demand more from their governments to deliver solutions.

While populations are exercising more potent public voices, governments will experience mounting pressure from economic constraints and a mix of demographic, environmental, and other challenges. Individually and collectively, these pressures will test states’ capacity and resilience, deplete budgets, and add to the complexity of governing.

Demographics and Human Development. Many countries will struggle to build on or even sustain the human development successes achieved in the past several decades because of setbacks from the ongoing global pandemic, slower global economic growth, the effects of conflict and climate, and more difficult steps required to meet higher development goals. Meanwhile, countries with aging populations and those with youthful and growing populations will each face unique sets of challenges associated with those demographics. Migration is likely to increase the salience of identity issues that divide societies in receiving countries and may fuel ethnic conflicts. Rapid urbanization—occurring mostly in Africa and Asia—will stress governments’ ability to provide adequate infrastructure, security, and resources for these growing cities.

Responding to Climate Change and Environmental Degradation will strain governments in every region. The impact will be particularly acute in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, where governments are already weak, stressed, or fragile. Wealthy countries will also increasingly face environmental costs and even disasters that challenge governments’ responsiveness and resources, potentially undermining public trust.

Economic Constraints. The expected trend of slowing economic growth is likely to strain the resources and capacity of governments to provide services. Governments are already saddled with debt on an unprecedented scale. In addition, rising or persistent inequality within many states, coupled with corruption, will threaten people’s faith in government and trust in one another.

Technological Change. Governments will be hard pressed to keep up with the pace of technological change and implement policies that harness the benefits and mitigate the risks and disruptions. Technological advances will also empower individuals and nonstate actors to challenge the role of the state in new ways.

(Informal settlements in Mumbai... - Click image to enlarge)

In the face of these challenges, existing systems and models of governance are proving inadequate to meet the expectations of populations. The result is a growing disequilibrium between public demands and governments’ ability to deliver economic opportunity and security. This public pessimism cuts across rightwing, leftwing, and centrist governments, democratic and authoritarian states, and populist and technocratic administrations. For instance, in Latin America and the Caribbean, public opinion surveys in 18 countries showed a significant decline in satisfaction with how democracy is performing in their countries from an average of 59 percent of respondents in 2010 to 40 percent in 2018. As publics grow skeptical of existing government systems, governments and societies are likely to struggle to agree on how to adapt or transform to address key goals, including advancing economic opportunities, addressing inequalities, and reducing crime and corruption.

The nature of these challenges and the government responses will vary across regions and countries. In South Asia, for instance, some countries will face a combination of slow economic growth that is likely to be insufficient to employ their expanding workforces, the effects of severe environmental degradation and climate change, and rising polarization. Meanwhile European countries are likely to contend with mounting debt, low productivity growth, aging and shrinking workforces, rural-urban divides, and possibly increasing inequality as well as fractured politics and debates over economic and fiscal policies at the national level and in the EU. In China, the central tension is whether the Chinese Communist Party can maintain control by delivering a growing economy, public health, and safety, while repressing dissent. The massive middle class in China is largely quiescent now; an economic slowdown could change this.

Many states are likely to remain stuck in an uneasy disequilibrium in which populations are unsatisfied with the existing system but unable to reach consensus on a path forward. A decade ago, the Arab Spring exposed serious shortcomings in the prevailing political orders, but in most countries in the region, a new social contract between state and society has yet to emerge. Similar to the Middle East, other regions could be headed toward a protracted and tumultuous process in part because citizens have lost faith in the ability of government institutions to solve problems. Even if states improve security and welfare in the aggregate, these gains and opportunities may be unevenly distributed, fueling discontent in seemingly more prosperous societies. For instance, from 2000-18, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries experienced overall growth in employment, but jobs were divided between high and low wages with little in the middle, many jobs became increasingly tenuous, and job growth varied significantly across regions and demographic groups.

POLITICAL VOLATILITY RISING

In coming years, this mismatch between governments’ abilities and publics’ expectations is likely to expand and lead to more political volatility, including growing polarization and populism within political systems, waves of activism and protest movements, and, in the most extreme cases, violence, internal conflict, or even state collapse. Variations in state capacity, ideology, and prior histories with mobilization will shape how and when public discontent translates into political volatility in each country.

Polarization and Populism. Polarization along ethnic, religious, and ideological lines is likely to remain strong, as political leaders and well-organized groups push a wide variety of broad goals and approaches that cut across economic, governance, social, identity, and international issues. In some countries, such polarization is likely to increase and reinforce political dysfunction and gridlock and heighten risks of political instability. Once established, severe polarization is difficult to reverse. Public dissatisfaction with mainstream politics for failing to address economic or social grievances has also led to the global rise in populism during the past several decades—measured in both the number of populist leaders in power and populist party vote shares worldwide. Although some populists will falter in office, the populist appeal is likely to endure as long as dissatisfaction, polarization, and fractured information landscapes persist. In addition, populism tends to surge after economic crises or changes in the ethnic or religious composition of a society from migration.

Protests. Antigovernment protests have increased globally since 2010, affecting every regime and government type. Although protests are a signal of political turbulence, they can also be a sign of democratic health and a force for democratization by pressing for accountability and political change. The protest phenomenon is likely to persist in cycles and waves because of the enduring nature of the underlying drivers, including ongoing public dissatisfaction and desire for systemic change, insufficient government responses, and pervasive technology to organize protests rapidly.

(Protests—seen here in Algeria—have surged worldwide in the past decade... - Click image to enlarge)

Political Violence, Internal Conflict, and State Collapse. During the next two decades, increased volatility is likely to lead to the breakdown of political order and outbreak of political violence in numerous countries, particularly in the developing world. As of 2020, 1.8 billion people—or 23 percent of the world’s population—lived in fragile contexts with weak governance, security, social, environmental, and economic conditions, according to an OECD estimate. This number is projected to grow to 2.2 billion—or 26 percent of the world’s population—by 2030. These states are mostly concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by the Middle East and North Africa, Asia, and Latin America. These areas will also face an increasing combination of conditions, including climate change, food insecurity, youthful and growing populations (in Africa), and rapid urbanization, that will exacerbate state fragility. Outbreaks of political violence or internal conflict are not limited to these fragile states, however, and are likely to appear even in historically more stable countries when political volatility grows severe.

DEMOCRACY UNDER PRESSURE AND AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES ALSO VULNERABLE

This volatile political climate creates vulnerabilities for all types of governments, from established liberal democracies to closed authoritarian systems. Adaptability and performance are likely to be key factors in the relative rise and fall of democratic and authoritarian governance during the next 20 years. Governments that harness new opportunities, adapt to rising pressures, manage growing social fragmentation, and deliver security and economic prosperity for their populations will preserve or strengthen their legitimacy, whereas those that fail will inspire competitors or demands for alternative models. Democracies will also have the advantage of drawing legitimacy from the fairness and inclusivity of their political systems—attributes harder to achieve in authoritarian systems.

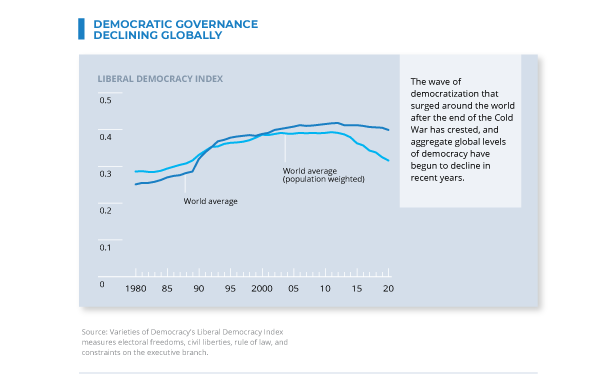

Democracy Eroding

The challenges governments face suggest there is a high risk that an ongoing trend in erosion of democratic governance will continue during at least the next decade and perhaps longer. This trend has been widespread—seen in established, wealthy, liberal democracies as well as less mature partial democracies. Key democratic traits, including freedom of expression and the press, judicial independence, and protections for minorities, are deteriorating globally with countries sliding in the direction of greater authoritarianism. The democracy promotion nongovernmental organization (NGO) Freedom House reported that 2020 was the 15th consecutive year of decline in political rights and civil liberties. Another respected measure of democracy worldwide, Varieties of Democracy, indicates that as of 2020, 34 percent of the world’s population were living in countries where democratic governance was declining, compared with 4 percent who were living in countries that were becoming more democratic.

(DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE DECLINING GLOBALLY - Click image to enlarge)

Several internal and external forces are driving this democratic erosion. In some Western democracies, public distrust of the capabilities and policies of established parties and elites, as well as anxieties about economic dislocations, status reversals, and immigration, have fueled the rise of illiberal leaders who are undermining democratic norms and institutions and civil liberties. In newer democracies—mostly in the developing world—that transitioned from authoritarian rule in the 1980s and 1990s, a mix of factors has led to democratic stagnation or backsliding, including weak state capacity, tenuous rule of law, fragile traditions of tolerance for opposition, high inequality, corruption, and militaries with a strong role in politics. Externally, China, Russia and other actors, in varying ways, are undermining democracies and supporting illiberal regimes. This support includes sharing technology and expertise for digital repression. In particular, some foreign actors are attempting to undermine public trust in elections, threatening the viability of democratic systems. Both internal and external actors are increasingly manipulating digital information and spreading disinformation to shape public views and achieve political objectives.

Looking forward, many democracies are likely to be vulnerable to further erosion and even collapse. An academic study of 75 democracies that experienced substantial democratic decline since 1994 found that 60 of them (80 percent) eventually became autocracies. However, the decline is not inexorable, and it may ultimately reflect a bad patch in a long cycle that has seen democracy advance and retreat with an overarching trend to more democracy during the past century. The long-term legitimacy of democratic systems hinges on two general conditions: maintaining a fair, inclusive, and equitable political process and delivering positive outcomes for populations. Addressing public concerns about corruption, elite capture, and inequality can help restore public trust and strengthen institutional legitimacy. In addition, providing effective services, economic stability, and personal security—historically advantages for democracies—increases public satisfaction. Beyond these basic governance benchmarks, demonstrating resilience to emerging global challenges will help restore and maintain public confidence.

Over the long term, the advance or retreat of democracy will depend in part on the relative power balance among major powers. Geopolitical competition, including efforts to influence or support political outcomes in other countries, relative success in delivering economic growth and public goods, and the extent of ideological contest between the Western democratic model and China’s techno-authoritarian system, will shape democratic trends around the world.

Authoritarian Regimes Will Face Vulnerabilities

Authoritarian regimes will face many of the same risks as democracies, and many may be less adaptable, making a sudden, violent change of government after a period of apparent stability more likely. Although authoritarian regimes in countries from China to the Middle East have demonstrated staying power, they have significant structural weaknesses, including widespread corruption, overreliance on commodities, and highly personalist leadership. Public protests are posing increasing threats to authoritarian regimes, toppling 10 regimes between 2010 and 2017; another 19 regimes were removed in elections, often held in response to mass protests. Corruption was a primary motivation behind many protests, and authoritarian regimes tend to be more corrupt than democracies. Authoritarian regimes that rely on raw commodities to finance their patronage networks and fuel their economies will be vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices, especially if energy transitions depress oil prices. Personalist authoritarian regimes—in which power is consolidated in one person or a small group—tend to be the most corrupt and erratic in decisionmaking, the least likely to plan for succession, and the most likely to start wars and escalate conflicts. Today the most common form of authoritarian regime is personalist—rising from 23 percent of dictatorships in 1988 to 40 percent in 2016—and other regimes, including in China and Saudi Arabia, are moving in that direction.

To try to quell, withstand, or address public discontent, authoritarian regimes are using new and traditional forms of coercion, cooptation, and legitimation. Technology has helped make authoritarian regimes more durable in recent years, in part because digitization and communication technologies make surveillance more pervasive and less costly. The flip side of these technological trends is that they have given populations the tools to circumvent digital repression and mobilize dissent. In addition to repression, regimes will rely on cooptation to convince critical allies to stay loyal, but this dynamic depends on more tenuous flows of resources. Many authoritarian governments will seek to build popular legitimacy through effective government performance and compelling ideologies. With their centralized power, some authoritarian regimes have demonstrated faster and more flexible responses to emerging challenges, but historically authoritarian governments have suffered from lack of innovation caused by misallocation of resources. Authoritarian regimes that deliver economic opportunities and maintain security may convince their publics that their system is better suited to dealing with the complexity and speed of tomorrow’s world.

(Ugandan officials operating a facial recognition surveillance system provided by a Chinese company. - Click image to enlarge)

ADAPTIVE APPROACHES TO GOVERNANCE: MORE ACTORS PROVIDING A WIDER RANGE OF SERVICES

As public needs and expectations mount, there is likely to be a growing shift toward adaptive approaches to governance that involve a broader set of actors outside state institutions delivering welfare and security. Nonstate actors, including private sector companies, NGOs, civil society groups, religious organizations, and insurgent and criminal networks, have long provided governance in all types of states. These roles are likely to expand to a wider range of actors and functions because of a combination of factors including: the failure of states to provide adequate governance; the increasing resources and reach of the private sector, NGOs, and individuals because of technology; and the growing complexity and number of public policy challenges that require multiple stakeholders to address. This shift is likely to produce some tensions and growing pains within states, as exemplified by illiberal regimes cracking down on civil society organizations or democracies seeking to regulate social media and operations of some nonstate actors.

Depending on the context and activity, nonstate actors will complement, compete with, and in some cases replace the state. The provision of governance outside state institutions does not necessarily pose a threat to central governments, nor does it diminish the overall quality of governance for the population. The roles and relationships between state and nonstate actors will depend on their relative capacity, penetration, and alignment with population expectations. From the Middle East to Africa and Latin America, insurgent groups and criminal organizations are filling in the governance gap and at times exploiting weak governments to expand their influence by providing employment and social services, ranging from healthcare and education to security and trash collection. In other cases particularly in Africa, international NGOs, some religiously based, augment the role of the state by providing health and education services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous examples of adaptive governance have appeared. Corporations, philanthropies, technology companies, and research and academic institutions have worked in concert with governments to produce breakthroughs at record speeds. Elsewhere, civil society organizations all over the world have filled gaps in government responses, providing humanitarian relief and welfare services. This role of nonstate actors in governance extends beyond providing services; for example, technology companies wield significant power in their control over information flows and networks with the ability to shape political discourse.

Local Governance More Consequential

Local governments are also likely to become increasingly important sources of governance innovation because of their ability to solve problems for their populations. Local governments generally have the advantage of proximity to the problems of their constituents, legitimacy, accountability, and the flexibility to customize responses; they also have less partisanship. Cities and subnational governments have greater ability than national governments to create and lead multisectoral networks involving various levels of government, private sector, and civil society; these partnerships have helped to revitalize some former industrial cities in the West. Local and city governments—increasingly organized into networks —will take action on international issues such as climate change and migration, getting ahead of national governments in some cases. As urban areas grow in population and as hubs for economic activity, technology, and innovation, these local governments are likely to gain increasing clout vis-a-vis national governments. Even in authoritarian regimes, local governance is likely to be a locus for problem solving but with different constraints.

(Bangkok, Thailand accounts for almost half of the country’s economic output. - Click image to enlarge)

Like national governments, local governments are likely to face budgetary constraints, particularly after the COVID-19 crisis. Cities in the developing world are likely to face significant financing gaps for infrastructure development and climate change adaptation. In addition, urbanization is likely to exacerbate urban-rural societal divides, while the expanding role for local and city governance may undermine policy coherence when local and national strategies for problem solving diverge.

(INNOVATION IN GOVERNANCE - Click image to enlarge)

RIPE FOR NEW OR SHIFTING MODELS?

The combination of widespread public discontent and major crises or shocks could create conditions that are ripe for significant shifts or transformations in the models, ideologies, or ways of governing. Historically, ideological shifts across regions have taken place at moments of catastrophic crisis, such as in the wake of a major war or economic collapse, because people are more willing to embrace bold systemic changes to address overarching problems. However, the emergence of a new unifying ideology or system—on the scale of communism or economic liberalism—is rare. Other stresses, such as another pandemic or a major environmental catastrophe, that expose governance shortcomings might create conditions ripe for new or alternative models to gain traction if widespread dysfunction is sustained.

Pervasive discontent and major crises probably are necessary forcing functions for transformations but not sufficient. Transforming discontent into something new also requires the combination of inspiring and unifying leadership with compelling ideas or ideology to build political coalitions and garner societal consensus. Short of a new ideology, new approaches—or even more combinations or blends of systems—could occur along several axes, from centralized to localized governance, from a strong state role to a strong nonstate role, from democratic to authoritarian, from secular to religious, or from nationalist to internationalist. These shifts or transformations would spur inevitable contestation between the constituencies holding onto the old orders and those embracing the new ones.

The precise nature of these shifts, transformations, or new models is uncertain and difficult to foresee. Some potential outcomes include: cities or subnational regions emerging as the focal point for governance if populations see local governments as more trustworthy and capable of solving problems than national governments; the private sector and other nonstate actors overtaking and displacing governments as the primary providers of welfare and security; democracy experiencing a revival if it proves more adaptive to the coming global challenges; or the world succumbing to an authoritarian wave partially inspired by China’s model of technology-driven authoritarian capitalism. Moreover, compelling new governance models or ideologies that have not yet been envisioned or identified could emerge and take hold.